Eight somber Muslims sat around white plastic tables on the gold-tinged red carpet of Sayyida Aisha Mosque in Sidon, Lebanon. Arabic sweets beckoned, but few partook. The seriousness of the occasion—reviewing their memories of Lebanon’s 15-year civil war that ended in 1990—seemed to make several uneasy. They did sip their tea.

Four were Lebanese native to Sidon. Four were Palestinian refugees. Several wore beards, some long and scraggly, others short and trimmed. One was a former fighter in the war. Another lost family members when a Christian militia massacred inhabitants in Tel al-Zaatar.

Beginning in 1975, Christians, Muslims, and Palestinians plunged Lebanon into a regional conflict that included Israel and Syria, leaving 150,000 dead. Those convening the meeting, a Lebanese evangelical and a Druze follower of Jesus, hoped to unravel the reasons behind the highly contested conflict. Their host, chief judge for the Sunni Muslim court in Sidon and imam of the mosque, lent his legitimacy to the sensitive proceedings.

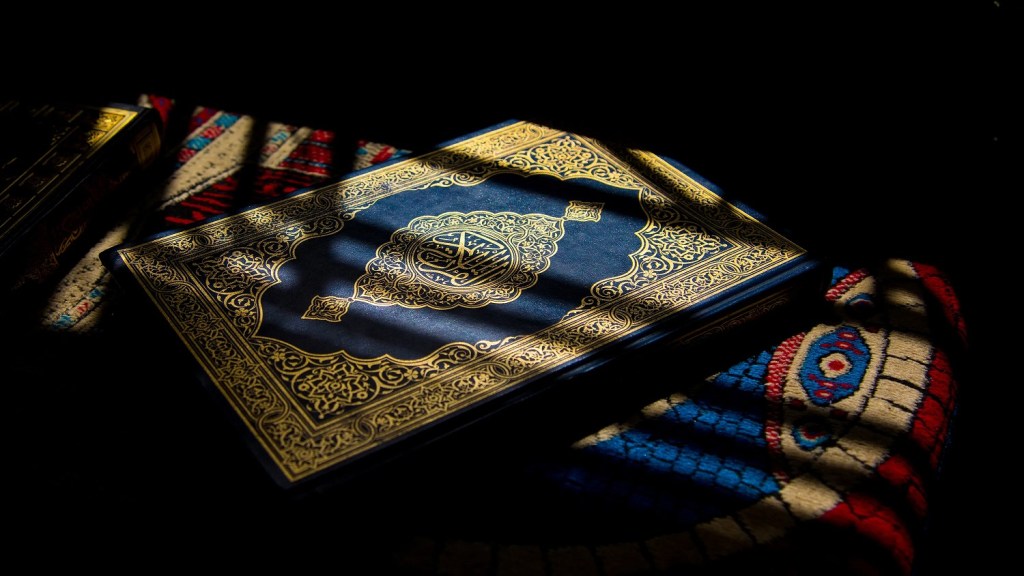

As participants received a 12-page document presenting Lebanese history that preceded the war, they were taken aback by reading a fully Christian perspective. But then the story shifted to Muslim perspectives, divided between Lebanese and Palestinian views. Three versions of history, none legitimized over the other.

Many Christians do not call Lebanon’s tragedy a civil war. They emphasize how Palestinian refugees brought local destruction in their fight against Israel. Meanwhile, Palestinians emphasize displacement from their homeland and their need for a base from which to fight Israel. Lebanese Muslims sympathized with Palestine but aimed to change a sectarian political order that disproportionately favored Christians.

When the group finished reading the document, the evangelical stood up.

“Which narrative do you sympathize with the most?” he asked.

Martin Accad, president of the Beirut-based Near East School of Theology, spoke in his capacity as founder of Action Research Associates (ARA), which is working on a project that presents civil war history through multiple narratives. Cofounder Chaden Hani took notes. Their project is unique because, in schools, history books end shortly after the country’s independence in 1943 and avoid discussion of the sectarian struggles that followed.

A few participants dominated the mosque conversation with their viewpoints. An elderly Palestinian former fighter mostly sat silent. Accad asked about their emotions, which prompted different responses. “Sadness at what happened,” said one. “Fear it might happen again,” said another. A third noted, “I am happy we are finally trying to talk objectively about what took place.”

To move on from the conflict, Parliament passed a general amnesty law in 1991 that pardoned all political and civil war–related crimes. Former militia leaders became politicians and ignored the peace accord to write a unified history textbook as each sect clung to its narrative.

In 1997, Lebanon mandated a new educational approach. After three years of work, the cabinet formally adopted the history curriculum. But it was never implemented due to political interference behind the scenes.

“History is written by the winners,” said Accad. “But there was no winner in Lebanon.” Christians and Muslims fought each other, and as allegiances shifted, each religion split into rival factions that clashed as well.

Accad said history became…

This article was originally published at Christianity Today, on December 18, 2025. Please click here to read the full text.