The oldest Protestant seminary in the Middle East has a new vision.

Officially founded in 1932 but with origins dating back to the 19th-century missionary movement, the Near East School of Theology (NEST) is operated by the Presbyterian, Anglican, Lutheran, and Armenian Evangelical denominations.

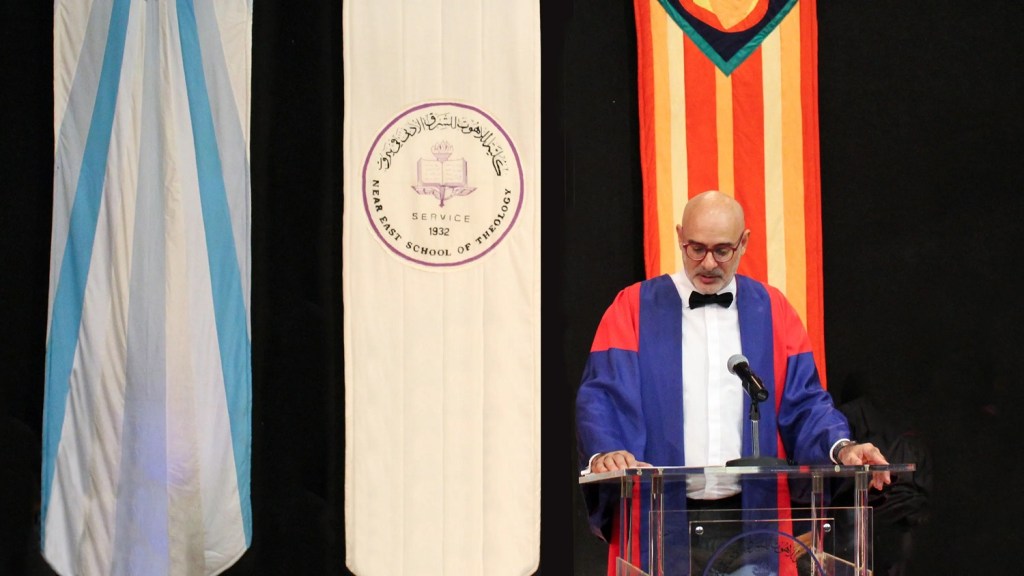

Installed this week, its 11th president is a nondenominational Lebanese evangelical.

Martin Accad, formerly academic dean at Arab Baptist Theological Seminary (ABTS), was installed on Sunday at the historic institution’s Beirut campus. He graduated from NEST in 1996 with a bachelor of theology degree, eventually earning his PhD from the University of Oxford. Awarded scholarships by the World Council of Churches and the evangelical Langham Partnership, Accad is a locally controversial theologian who, like NEST, straddles the liberal-conservative dichotomy.

Author of Sacred Misinterpretation: Reaching Across the Christian-Muslim Divide, Accad has urged believers to approach Islam in a manner that avoids the twin pitfalls of syncretism and polemics. But before joining NEST he resigned his prior academic position at ABTS to apply his biblical convictions within Lebanon’s contested political scene. Creating a research center, his last four years have been spent in pursuit of reconciliation between Lebanon’s often-divided sectarian communities.

Accad will now bring his vision to a new generation of Middle East seminarians.

Although doing public theology is novel for the institution, NEST has long sought, with some struggle, to balance the two streams of its early predecessors’ commitments to evangelistic outreach and service-oriented witness. Its founding in 1932 resulted from a merger of two programs, each with its own distinctives.

One stream of NEST’s roots dates to 1856, when American missionaries began what Accad describes as a discipleship training program in the mountains of Lebanon. Along with providing pastoral development, it functioned as a mission station for sharing the gospel in local villages with non-Protestant Christians and diverse Muslim communities. Its remote location was also designed to isolate these early “seminarians” from the corruption of city life in Beirut.

American outreach to Armenians and Arabs in the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey) led to the creation of similar schools beginning in 1839. After the Armenian genocide in World War I, these efforts relocated to Athens where they coalesced into a seminary that adopted an ecumenical, Enlightenment-informed model, emphasizing the importance of social service. This was especially true in its approach to Islam—sympathetic and comparative with an eye toward reconciliation.

The merger of these two programs created NEST, which eventually settled in the cosmopolitan Hamra neighborhood of Lebanon’s capital. Although it is situated near three historic Protestant liberal arts colleges—now known as the American University of Beirut (AUB), the Lebanese American University (LAU), and the Armenian-led Haigazian University—early cooperation was shattered by the Lebanese civil war in 1975 and has not been re-established.

Accad wants to restore this collaboration and embody an integration of scholarship and discipleship. CT spoke with him about Protestant distinctives, “electric shock” pedagogy, and how to understand the mainline-evangelical divide in the Middle East.

Why does serving as president of NEST appeal to you?

We need to rethink what it means to be a seminary student today. This question is a key issue globally, but especially in the Middle East. Ideally, the seminary leads the church to be relevant in society. This requires beginning with society and determining its needs. And then the seminary addresses the church—what does the pastor need? Finally, it works backward and designs a program to fit this profile.

Historically, NEST has been an ordination track. This is the traditional model, and it is still necessary if the church believes that it is. But I want to explore with the churches their vision for seminary training, for congregational service, and for regional witness—and how NEST can help prepare leaders to implement this vision.

How do you plan to prepare leaders to serve the church?

Nontraditional, focused tracks are becoming the way people want to learn. Accrediting bodies speak of micro-credentials that may contribute toward academic goals but have value in and of themselves and fit into the bigger puzzle of what students want to do with their lives.

But this system of training should not be only for evangelicals. I want NEST to attract…

This article was originally published at Christianity Today on September 27, 2024. Please click here to read the full text.