Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: Getty, Unsplash

This is part two of the Eddy family’s story. To read about the Eddy missionaries in Sidon, click here.

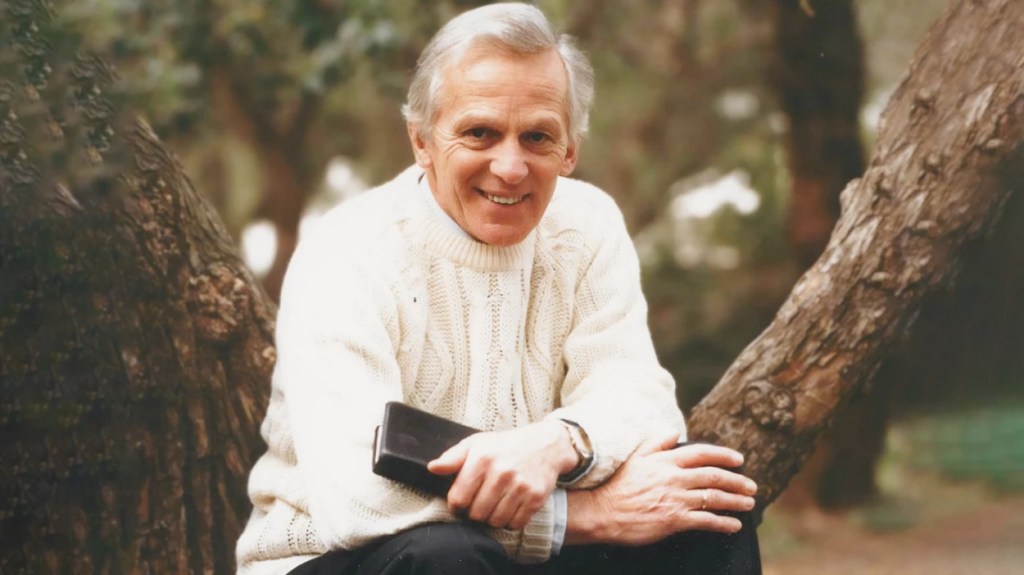

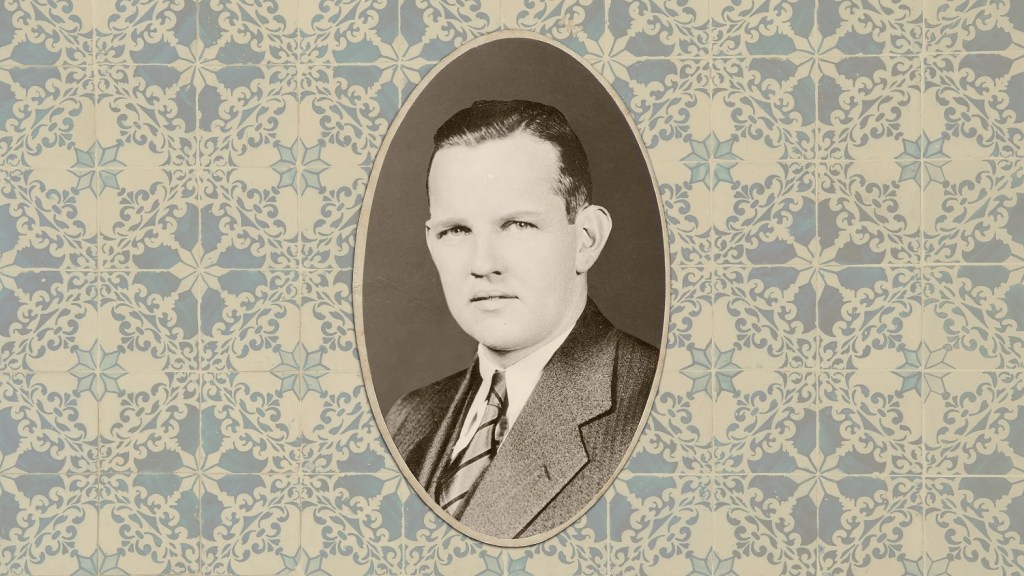

William Alfred Eddy was an American hero. Nicknamed “Bill,” he received the Navy Cross, two Silver Stars, and two Purple Hearts for his service in World War I. During World War II, he quit his job as a college president to reenlist and helped plan the Allied invasion of North Africa. Later, as a diplomat, he advanced Franklin Roosevelt’s agenda by forging the US alliance with Saudi Arabia.

“Eddy (hereafter ‘Bill’) managed to pack four or five lives into a single lifetime,” wrote Princeton University’s alumni magazine about its former doctoral graduate. One of those lives began as a missionary kid to an American family in the Levant.

Top of Form

Part one of this series chronicled the Eddys’ multigenerational service in Lebanon, particularly its southern city of Sidon. Active in evangelism, education, and medical work, some of the Eddys died on the field and are buried in local evangelical cemeteries.

So was Bill. But while his gravestone inscription marks the rank of colonel in the US Marine Corps, it doesn’t include the number of years he “served the Lord” like his family members’ gravestones. The modern Eddy biographer, Muhammad Abu Zaid, didn’t criticize either approach. He called Bill the American “Lawrence of Arabia” and sympathized with his family’s earlier religious commitments.

In Forgotten Pages from the Ancient History of Sidon, published in Arabic by the Baptists of Lebanon, the president of the Sunni Muslim Sharia Law Court in Sidon described the religious and social development of Protestant ministry through building churches, schools, and clinics. Bill, he contrasted, pursued his country’s political objectives in the Arab world.

But today, evangelicals number only one percent of the Lebanese population. And polls indicate America’s poor reputation in the Middle East. Secular or spiritual, how does Abu Zaid evaluate the Eddys’ presence in his homeland?

“I felt sorry for them,” he told CT. “They didn’t succeed.”

The story continues from part one, with William Alfred, age 10, watching his father William King die suddenly on a preaching tour. After this traumatic experience, Bill moved to America and eventually enrolled in a Presbyterian university. Two years later, he transferred to Princeton and graduated in 1917. When the US entered World War I, he enlisted, fought in the tide-turning battle of Belleau Wood, and suffered a leg injury that made him limp for the rest of his life. After receiving his PhD in 1922, he joined the American University in Cairo, and one year later, he became chair of the English department.

Bill remained devout in his Christian faith—he even…

This article was originally published at Christianity Today on September 5, 2025. Please click here to read the full text.