Sitting with a student distraught by religious war, a God-fearing academic lamented the chaos in Syria, the destruction of Iraq, and the existential tensions seemingly ever-present in the Holy Land.

“What a great fortune it would be if … every man on earth could be under one religion,” he said. “[Then] there would be no more rancor or ill will among men, who hate each other because of the contrariness of beliefs.”

The academic’s answer, unfortunately, underestimates the human capacity for conflict. Beyond the bloody geopolitics, Islam, Christianity, and Judaism have split into sects and factions, to the point of killing fellow believers who share the same text yet hold different beliefs.

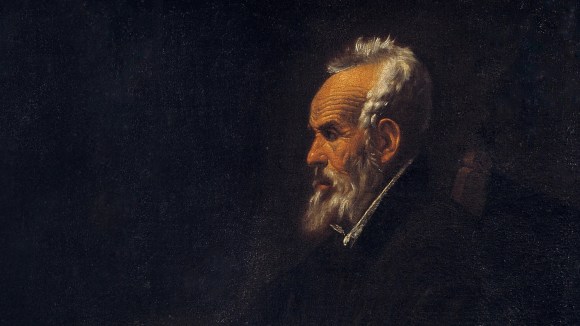

But for some, the “rancor and ill will” have prompted a corrective impulse to unite the faiths through interfaith dialogue. And the impulse is not new. The God-fearing academic? He’s a character from a book written in the 13th century by Ramon Llull, a Franciscan hermit and early proponent of an initiative still controversial among many believers today. Countercultural even then, The Book of the Gentile and the Three Wise Men addressed a world severely lacking in peaceful religious pluralism.

When Llull published his book in the 1270s, Crusaders were strengthening castles in Syria. The Mongol horde had sacked Muslim Baghdad—but then suffered defeat in Palestine, in the fields of Galilee. Llull wrote from what is now Spain, during the Reconquista, a military campaign to restore the Iberian Peninsula to Christendom. The Muslim realm, which they named Al-Andalus and became known as Andalucia, had been comparatively tolerant of Christians and Jews.

Llull lived on the island of Majorca, where his father settled after James I of Aragon declared victory in 1229. In the decades that followed, Christian kings in the liberated lands increased restrictions on non-Christian monotheists resident since the 8th century Islamic conquest. Some they forcibly converted, and within a few centuries, they expelled nearly all Muslims and Jews.

Llull, writing in Latin, Arabic, and his native Catalan, advocated for converting the non-Christians by rational argument, not the sword. While he did defend the Christian conquest of Muslim lands, he also founded missionary schools and traveled to North Africa, where he disputed with Islamic scholars.

Few of his contemporaries…

This article was originally published by Christianity Today on July 22, 2025. Please click here to read the full text.