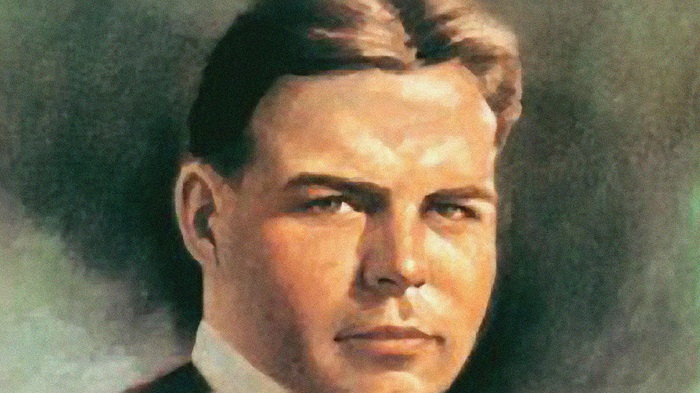

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: Courtesy of Nick Eddy

Pastor Michael Sbeit stood pensively in front of the marble gravestone in the evangelical cemetery of Sidon, a Lebanese city 25 miles south of Beirut. Mediterranean Cypress trees offered shade from the sweltering summer heat, while their fallen brown needles covered the ground and obscured the inscription engraved in both English and Arabic:

William King Eddy

Born March 13, 1854

Died Nov. 4, 1906

Served the Lord in Syria 28 years

Next to the grave of William King Eddy (hereafter “King”), is the grave of his wife, Elizabeth Nelson Eddy. Her tombstone honors her 49 years of service. Several feet away lies the body of their son, William “Bill” Alfred Eddy, who died in 1962.

The Eddys were an American family who originally came as Protestant missionaries to late 19th-century Lebanon, then part of the Syrian region of the Ottoman Empire. Several family members, including King’s sister Mary Pierson Eddy, and their father William Woodbridge Eddy (hereafter “Woodbridge”) are buried in Beirut.

“They were pioneers of our church,” said Sbeit, who leads the Presbyterian congregation the Eddys’ missionary colleagues founded in Sidon. “We don’t have many like them anymore.”

Two generations of Eddys shared the gospel, built schools, and offered healthcare. The last of their line in Lebanon left a more colorful legacy. William Alfred Eddy’s gravestone notes nothing about service to the Lord and instead displays his rank of colonel in the US Marine Corps.

“Bill loved this city,” said Sbeit. “But he was different.”

This two-part story chronicles the Eddy family’s multigenerational commitment to Lebanon. The family’s modern biographer is Muslim: Sheikh Muhammad Abu Zaid, president of the Sunni Sharia Law Court in Sidon. In Forgotten Pages from the Ancient History of Sidon, he expresses his deep appreciation for their foreign service.

“It is not how we look at the Eddys,” he said. “But how they looked at us.”

Abu Zaid’s sympathetic portrayal of Protestant missionaries contrasts with the more conflicted views that many Lebanese Muslims and Christians have held. Some view them as “sheep stealers” trying to convert the original Catholic, Orthodox, Sunni, Shiite, or Druze populations. Others see them as Western agents advancing America’s political agenda. Still others defend them, citing their years of devoted social service. The Eddys offer evidence each narrative could note.

The family’s story began when Chauncey Eddy, a Presbyterian pastor from New York joined the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in 1823. But when poor health impeded a potential missionary career, he prayed that God would call his children in his stead. His son Woodbridge and his daughter-in-law Hannah moved to the Levant in 1851, a year after the Ottoman sultan issued a decree to include the Protestant faith among the empire’s legally recognized sects.

The couple’s ministry started in Aleppo by learning Arabic before moving to the Lebanese mountain village of Kfarshima. In 1857, Woodbridge and Hannah moved south to Sidon, where they served in an evangelical church planted two years earlier. They replaced missionary Cornelius van Dyke, who left to complete a translation of Arabic Bible still cherished by many Middle Eastern Christians today.

Chauncey visited his son a year later, delighted at the fulfillment of his prayers. He even…

This article was originally published at Christianity Today on September 4, 2025. Please click here to read the full text.