Names don’t work the same in every culture.

We realized this six years ago, when our oldest daughter came home from her first days of school with “Emma Jaison” printed on her books. Her name is Emma Hope Casper, which I clearly wrote on all her official forms.

But I also filled out the ever-important question of her father’s name, my husband, Jayson. As per Egyptian pattern, her name became Emma Jayson, though in practice Ema or Amy, Jaison or Jasen, depending on how they guessed these strange names to be spelled.

A quick lesson in the Egyptian naming system is required. When a baby is born, parents choose the first name, just as they would in America. But that is the choice available, and the rest of the name is determined by family.

Every baby’s second name is its father’s name, even if she is a girl. The third name is the baby’s grandfather’s name—that of the father’s father. The fourth and final name for official paperwork is that of the great-grandfather, and unofficially stretches back through the generations.

To be honest, we are still confused about any actual “family name”. Some people seem to have something to correspond with Smith or MacDonald, although it would be something along the lines of Masri (from Egypt) or Tantawi (from Tanta). But we can’t quite figure out how that works with the pattern above.

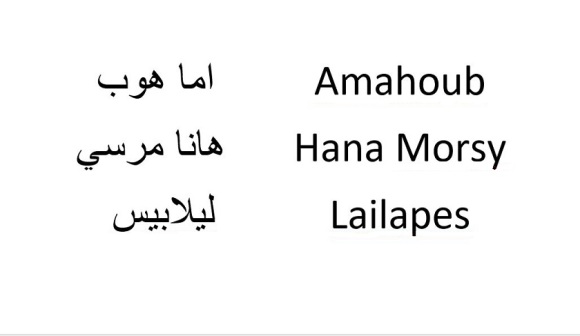

Each of our three daughters have similarly returned from kindergarten with their name changed. Our second became Hannah Jayson, though alternately spelled: Hanah, Hana, or Hanna.

Trying to get it right in discussion with school administration, our third daughter’s first name, Layla, got combined with her second, Peace. But her papers came back: Lailapes Jaison. I almost couldn’t figure out what it said.

Granted, transliteration between English and Arabic isn’t easy. But he mix-ups in name have sometimes bothered our girls. A simple name like Emma Hope has become Amahoub. Hannah Mercy was eventually spelled correctly, with her a different issue emerged.

In kindergarten, Hannah was known only as Hannah Jayson, but when she entered first grade, they added her actual middle name. This happened the same year that the former president Mohamed Morsy was deposed.

But when you write Mercy in Arabic script it looks just like Morsy, since Arabic writing leaves out the short vowels. And since the word “mercy” in English looks nothing like its translation in Arabic (rahma), everyone assumed she was similarly named to the Muslim Brotherhood leader.

Plenty of people here hated the Brotherhood, but Morsi is a fine and common name—among Muslims. While plenty of names have no religious marker, Abanoub or Shenouda signify a Christian, while Mohamed or Morsi indicate the child is a Muslim.

So the teachers wondered: Why is Hannah Morsy enrolled in the Christian religion class?

Click here to read more about our kids and religious education in Egypt.

Even more confusing for the teachers is how Emma “Hobe” and Hannah “Morsy” are sisters to begin with, with different names for their father. Add in Lailapes Jaison and you really confuse them!

We thought we would make things easier for our son Alexander, who is now entering kindergarten.

Click here to read the different naming options we considered, with pros and cons for each in Egypt.

My husband’s middle name is the same as his father’s, so to honor both the family and the Egyptian pattern, we did the same. He is Alexander Jayson (father’s name) Charles (grandfather’s name). His last name is still Casper, as we can’t imitate them in everything.

But it won’t be that easy. We commonly call him by the Arabic equivalent of Alexander, Iskander. He goes by both, and much as a four-and-a-half-year-old understands these things, he knows they are both his names.

But when he gets to school, what will he say his name is? Will he write Iskander in Arabic class, but Alexander in English? And how many people will just call him Alex, anyway?

Despite the confusion for each of our kids, we teach them their names were chosen with care. We display them in our living room, that they might be esteemed by child and guest alike.

English-speaking friends sometimes curiously notice the semi-strange middle names, and Arabic-speaking friends are often altogether confused. But wholesome discussion usually follows.

Hope, Mercy, and Peace—each a desirable virtue for life, paired with a corresponding Bible verse we trust they will internalize.

Our son’s pattern is different, and his sign requires more explanation. Alexander was the son of Simon of Cyrene, who carried Jesus’ cross. Of his two middle names, may he follow and become a third generation of faith.

Children grow old and develop their character. But a name is the one thing we give them they keep their whole lives. Their identity will be shaped by many, and their path is their own.

But we have the responsibility to shape their foundation, beginning with that first official form.

Our Hope is that they grow up with the Mercy to let others misunderstand them, the internal Peace to know who they truly are, and a family history to teach them whose cross they are privileged to carry.

4 replies on “Why Egyptians Get Confused by Our American Children’s Names”

I’ve had to get used to the name thing over here in Qatar as well. I have 5 Mohammed’s in my class and two students with the exact same first and last name. The only way I don’t confuse them and their paperwork is to call them by their middle name and guess what, that adds another Mohammed to the class. Your girls are getting a life lesson about culture that no reading of books could give them.

LikeLike

Thanks, Phillygirl. I’m fascinated by Qatar. Soak it up and learn all you can.

LikeLike

My mother is a genealogist and names are so important. There is a naming scheme in the US but it is being forgotten… My sons were named accordingly. The 1st son is named after his maternal grandfather and the 2nd son after his paternal grandfather… Looking at the family tree it is obvious where they belong just based on their names.

LikeLike

Would you say that scheme was adopted by many, or your family’s tradition? Very similar to here, and yes, US family culture does seem to be losing touch with the importance of generations.

LikeLike